Expanding

Economic Opportunities

in the Paraguayan Chaco

Three women sit near a pile of carob fruits, wearing masks and hair nets. They pick a few of them out, separating those they are about to grind into carob flour, filling large white bags that take most of the room. The flour is used for baking cakes, crackers, bread, and other goods and has seen growing demand. Coffee shops, restaurants, and organic produce stores use it for their dishes or sell it for high prices in Paraguay’s capital city, Asunción. Most of it is produced in the Chaco region by women from the native Nivaclé communities, and for a long time, they have relied on outside distributors to take their flour to the city. Now, they are doing it online.

“With technology, I can sell my produce elsewhere,” says Rogelia Pérez, a representative of the Fa’ay Lhavoquey—the Women Carob Harvesters Group. “I post it on social media, and people place orders.”

The Nivaclé are Indigenous people living in lands across the South American Chaco, in Paraguay, northern Argentina, and southern Bolivia. Funded by the Internet Society, the NANUM Connected Women Project—a transnational and multi-organization initiative to connect Indigenous women living in the Chaco—worked with nearly twenty Nivaclé communities in Paraguay’s Boquerón department. There, carob harvesting is their main occupation and one that brings promises of economic opportunities.

But before the NANUM Connected Women initiative started work, the communities were digitally isolated. Connectivity was scarce, and in the few places where it was available, it was more expensive than people could afford. The service was sufferable at best. Not many people, including the teachers in the local schools, had Internet-enabled devices. Both children and faculty were struggling to keep up with a connected world in an unconnected reality.

Today, we need the Internet. People have the right to use it, and we, Indigenous peoples, also have this right. The Internet will offer us a path to develop new skills.”

A Community of Networks

Although operators and the local government were aware of their struggle, little had changed for years. That is until the Fa’ay Lhavoquey—the Women Carob Harvesters Group—heard about a community network project supported by the Internet Society and the NANUM Connected Women initiative that connected other communities in the Chaco.

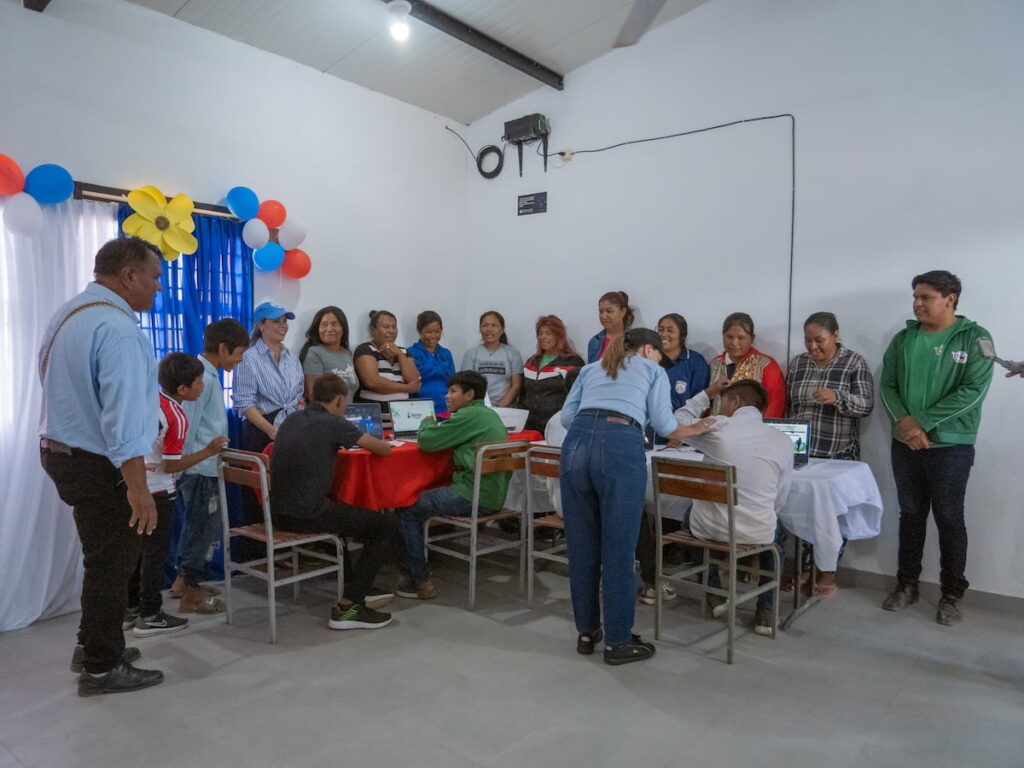

“These women have other associates spread around the Nivaclé lands, in about twenty communities. They were aware of the work we did and that we were building a NANUM center in Samaria,” says Mariana Franco, Country Manager for NANUM Paraguay. “They asked if it was possible to bring the Internet to other women. We presented the concept of community networks, and the women met across their communities to decide which were the critical spots to connect. “

We presented the concept of community networks, and the women met across their communities to decide which were the critical spots to connect.”

We are a group formed in 2019. We started with seven women and have been growing since. Now, we are around 30.”

After concluding the network in Samaria, the women agreed to connect three other communities: Jericó, Jope, and La Abundancia.

Following their decision, the technicians, led by Hector Matiauda of the Internet Society Paraguay Chapter, started planning the infrastructure. Since Paraguay recently passed legislation in support of Indigenous connectivity, the team was able to connect the local network to the rest of the Internet at no cost, working directly with the Paraguayan government. This supports their long-term sustainability.

Harvesting Change

The team concluded work for all communities in February 2024.

The Samaria community inaugurated a connectivity center in the “Women’s Home”, where they work in handicraft. Jericó now has a new digital inclusion room, with new equipment and Wi-Fi service covering the community’s main square. In Jope, the elementary school—the only school there—now has Internet, along with a digital inclusion room with equipment open for the community to use. In La Abundancia, the initiative connected a middle school with nearly 300 students and built a digital inclusion center at the community’s radio station.

Finally, the NANUM team expanded connectivity to a research center called TEMA—Human Habitat Improvement Workshop, or Taller para Mellora del Habitat Humano in Spanish—which teaches local residents skills such as improving irrigation, building water filters, in addition to providing places where researchers coming from other communities can rent and sleep.

Since the backhaul is free, the low fees charged support the maintenance and expansion of the existing network.

After we presented the community networks model at first, people were excited to learn they could have better service and keep the money flowing within their communities.”

A Promising Future

The next challenge is building the digital skills of the communities where many people are using digital devices and the Internet for the first time. To address this, Grupo Sunu—the organization executing the NANUM initiative in Paraguay—is taking advantage of the connectivity to host weekly online skills development workshops, mentorships, and even private classes. Once a month, they focus sessions on reinforcing learnings or advancing in something they might not have had time to cover. In addition to that, every two months, they offer one learning experience in which all communities join.

“It’s the first time we are using this technology,” says Elizabeth Pérez, part of the Fa’ay Lhavoquey. “Over time, people have begun to understand how to use it. They like it, and we are organizing spreadsheets of our sales.”

“Every Tuesday and Thursday, we meet and learn about technology,” says Rogelia Pérez. “One of the elderly women was illiterate her whole life. Now, using a computer, she learned how to spell her name.”

Help Connect the Unconnected

Image copyright:

© José Elizeche