In August 2017, a new botnet called WireX appeared and began causing damage by launching significant DDoS attacks. The botnet counted tens of thousands of nodes, most of which appeared to be hacked Android mobile devices.

There are a few important aspects of this story.

First, tracking the botnet down and mitigating its activities was part of a wide collaborative effort by several tech companies. Researchers from Akamai, Cloudflare, Flashpoint, Google, Oracle Dyn, RiskIQ, Team Cymru, and other organizations cooperated to combat this botnet. This is a great example of Collaborative Security in practice.

Second, while researchers shared the data, analysed the signatures, and were able to track a set of malware apps, Google played an important role in cleaning them up from the Play Store and infected devices.

Its Verify Apps is a cloud-based service that proactively checks every application prior to install to determine if the application is potentially harmful, and subsequently rechecks devices regularly to help ensure they’re safe. Verify Apps checks more than 6 billion instances of installed applications and scans around 400 million devices per day.

In the case of WireX, the apps had previously passed the checks. But thanks to the researcher’s findings, Google was able to identify approximately 300 already deployed apps, block them from the Play Store, and take action to remove them from all affected devices.

How does this relate to the IoT and home automation?

There are similarities between future Internet of Things (IoT) systems and today’s smartphone ecosystem. Smart objects correspond to various phone components – a camera, a touchpad, a barometer, a GPS receiver, data storage. Both rely on apps to control and automate the “things”. The role of a mobile OS and app store is played by middleware, or “platforms”, like HomeKit, IoTivity and SmartThings. And partly by your home network, but let us talk about that a bit later.

Like in the WireX story above, the platforms can play a very important role in securing home automation systems.

First of all – why is a platform needed? There are plenty of smart things on the market that only require a WiFi connection and an app to control it. But as the IoT penetrates our homes, we don’t want a separate app for each device, do we? We want a cohesive system that will control the ambience of our homes – temperature, humidity, lighting, sounds, and security. All depending on each other, the time, and our own mood.

That is where platforms come in handy – all devices use the same protocol and can all be controlled and programmed from a single app. They can exchange data through that platform, so the controlling app can make informed decisions.

These platforms are appealing because they simplify the user experience: they hide complexity and scale and automate all management.

For example, Apple’s HomeKit integrates iOS, tvOS, and watchOS devices with home automation accessories, using a device-independent protocol. It enables an app to coordinate and control accessories from multiple vendors, presenting a coherent, user-focused interface. And a “home hub” (4th generation Apple TV or an iPad) enables automation/programming and remote access to your smart home.

HomeKit is built with Security by Design. Its main protocol, HAP (HomeKit Accessory Protocol), enables strong encryption for data transmission, local secret key generation and storage, and secure pairing using a Secure Remote Password (SRP) protocol that eliminates drawbacks of the traditional password-based authentication methods.

A manufacturer of a HomeKit accessory that will be distributed or sold must be certified under the MFi (Made for iPhone/iPod/iPad) licensing program. MFi is a collection of security specifications and hardware requirements set by Apple that must be met before a third-party device can be approved to work with HomeKit or any other Apple software or devices. Apple’s checks are rigorous, so the “Works with Apple HomeKit” logo is a sign of high security standards.

Apple’s HomeKit is an example that demonstrates the potential platforms have or may have in securing the IoT.

There is an important caveat here: many of these platforms are proprietary and may cause a lock in, much in the same way that users tend to lock into an Apple or Android universe on their phones.

And another caveat: While HomeKit is secure and devices interact through that platform in a secure way, this is not the only way they can communicate, or be accessed. Specifically:

- Vendors are certainly interested in providing their own direct applications, unlocking “special” features not available through HomeKit.

- Apple only checks for device and software compliance to its own specifications, and does not perform an overall security assessment. Although, the ”Works with Apple HomeKit” mark is still a sign of a good security posture, theoretically it is possible to leave a telnet port open with admin/admin as credentials, for example.

So, how can we close these potentially open doors?

There are a few things that can help:

- Platform vendors can further strengthen their certification programmes and include the overall security of certified devices in their assessment. Their programmes are an effective way to promote baseline security norms, such as the Internet Society Online Trust Alliance IoT Trust Framework that includes 37 principles addressing privacy, security, and sustainability of IoT systems.

This should make sense. If security is a market differentiator, leaving vulnerabilities in a system otherwise operating on state-of-the-art security standards diminishes the whole effort. If a HomeKit-operated system is hacked, there is little excuse that this didn’t happen through the HomeKit platform itself.

- Users should deploy tools to monitor the health of their home network and sanitise it as needed. We are used to having anti-virus software running on our computers and smartphones, but do we run anything like this in our home network? Solutions like SENSE from F-Secure and the Turris project can help.

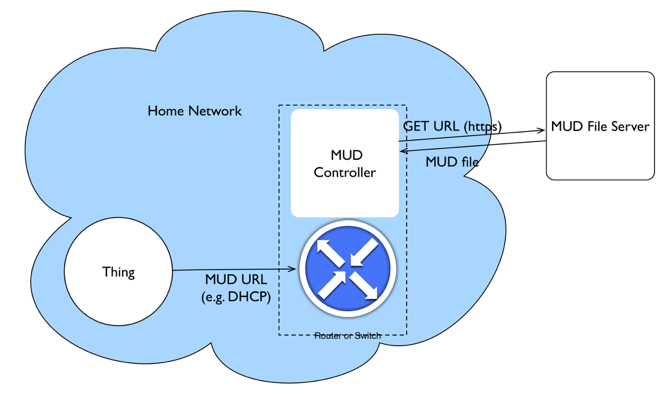

- The network itself can be informed upfront what to expect from a device. This can be complementary to points 1 and 2 and integrated in these approaches. One of the potential solutions is Cisco-proposed Manufacturer Usage Description (MUD) framework, now being discussed in the IETF.

The idea is that the device manufacturer provides a description of what sort of communications a device is designed to have. For example:

Allow access to devices of the same manufacturer

Allow access to and from controllers who need to speak COAP

Allow access to local DNS/DHCP

Deny all other access

During the initialization process, the device sends the URL where the corresponding MUD file is located. The MUD controller, which can be part of a home router or security firewall, downloads the XML file from the server. It is assumed that the MUD file is provided by the device manufacturer and is protected by a digital signature that allows the controller to verify the authenticity of the specification.

Next, the controller creates a security policy for the class of device described in the manufacturer’s MUD file. Approved communications are allowed and everything else is denied. The controller, upon approval from the network administrator, then merges the MUD information into the existing network policy.

And I haven’t even mentioned regulation

In a rapidly evolving ecosystem like the IoT, and especially smart homes, applying regulation directly may not be effective and may stifle innovation. But governments can help by fostering an environment where market forces can make useful and timely contributions to security and safety. I think the examples we discussed in this article demonstrate that such market forces exist.