Ever wonder if your next doctor’s appointment will result in jail time? Luckily most of us never have to think about that. But LGBT Tech Executive Director Chris Wood says for people in countries where their truth is outlawed, the prospect of finding a trusted healthcare provider without encrypted messaging apps is worse than grim. It could be deadly.

Efforts to weaken encryption threaten our ability to keep our most vulnerable communities safe online. As the best tool available to protect our digital security, encryption helps ensure that data and messages are kept private and make it much more difficult for outside parties to get access to sensitive information. Encryption helps ensure that your digital bank transactions are secure, your passwords are kept safe, and your stored data can’t be accessed by any unintended parties.

This security tool protects all Internet users, but it is critical for vulnerable communities. For example, there is an alarming and growing threat of abusive partners using Internet-connected devices and other online tools to surveil and control their partners. This can make it even more difficult for victims to seek help. However, by using devices and services that encrypt web traffic, communications, and location info, victims can protect their privacy and seek help without fear of a partner reading or accessing documents and chats at a later time.

We’ve already seen what can happen when security is weakened. Take the TSA luggage lock, which has become a favorite example of why “exceptional access” for law enforcement doesn’t always pan out as planned. These locks were supposed to only allow verified TSA agents to access the contents of your suitcase, but after an agent posted a picture of a key online, people copied it and made it readily available for purchase or to 3D print. The agent made an understandable mistake that probably seemed harmless at first. But that’s the problem. We’re human, and we make mistakes. When it comes to security, those mistakes can have huge impacts on all of us – particularly those in vulnerable communities.

Over the last several years, there has been a debate in the United States and around the world about the use of encrypted technologies. Many technologists, academics, manufacturers, civil society, and others have long fought to ensure devices and software are as secure as possible through encryption. However, some individuals, particularly those in government or law enforcement, have argued that there are times when actors – such as themselves – may need to bypass this critical security measure.

But there’s a problem with that. Encryption is not a technology that can be bypassed sometimes. It either works or it doesn’t. Saying that there should be a way to weaken it for only specific people in specific situations is a lot like saying, “you should leave a key under the mat to your front door, just in case there’s an emergency and the police need to come in.” That sounds great in theory, but what bad guy wouldn’t think to look under the mat, take the key, and create the bad situation in the first place?

It’s important to have conversations about encryption and protect it against attempts to create exceptional access measures and any other type of backdoor. Whether you realize it or not, we use and rely on encrypted services to keep ourselves and our data safe every single day. This is especially true for people from marginalized and vulnerable communities, several of which we heard from at a briefing event on October 25.

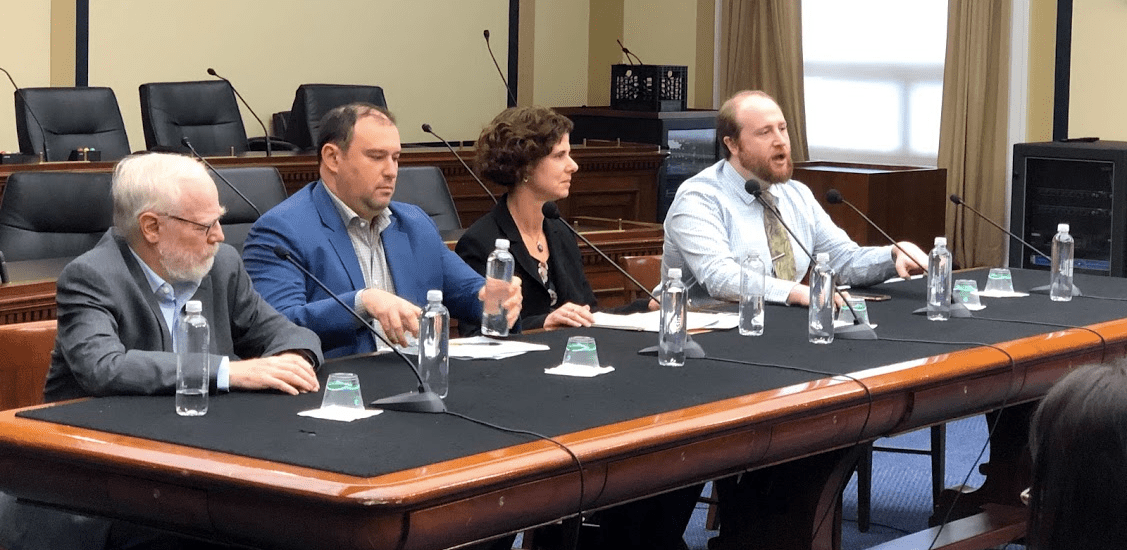

The Internet Society partnered with the Center for Democracy and Technology, the Internet Society Greater Washington DC Chapter, LGBT Tech, and New America’s Open Technology Institute to host Encryption Briefing: Understanding It’s Technical and Human Elements. This event consisted of two sessions: one on the technical elements that make encryption work and one on the ways it protects vulnerable populations, including the LGBTQ+ community, retirees, journalists, and many others.

Panelists from our partner organizations – along with Hispanic Technology & Telecommunications Partnership, the Committee to Protect Journalists, AARP, Apple, and Columbia University – discussed the different uses of encryption in their communities, how the technology works, and who holds the keys.

This last point is particularly important because whomever holds the key to unlock a user’s encrypted information has the ability to view and use it. Panelists during both sessions noted that security professionals today aim to create and deploy security by designing products and services that bring that key closer to the end user. With that key, end users have full control over their data, communications, and documents.

For example, Apple devices give users the key, but Apple does not have a copy of that key themselves. As Jeff Ratner, Senior Policy Counsel at Apple, noted during the panel, “if we don’t have the key, no one can take it from us.” That principle keeps users more secure because it limits the risk of the key being stolen in a breach or a rogue employee accessing their devices or information.

Consumers want to protect their data and their privacy, and companies are beginning to respond to that demand. Users know that using the Internet has inherent risks, and the more steps a company can take to minimize those risks – from malicious actors, untrustworthy individuals, or even governments – the better.

As LGBT Tech’s Chris Wood noted on the first panel, if manufacturers and developers don’t have trust and accountability, consumers won’t use their systems. It often only takes a couple of high-profile breaches or mismanagements of data and information for users to turn away from a particular product or service, especially for new or developing enterprises.

Participants also emphasized many times that we already face significant security challenges and encryption is our best tool to mitigate that risk. Susan Bradford Franklin, Policy Director for New America’s Open Technology Institute and Co-Director of New America’s Cybersecurity Initiative, noted that one of the largest security threats we face comes from vulnerabilities accidentally built into devices and services. Developers have to dedicate significant time and resources to address these issues, and they are unlikely to be able to fully protect users if they must also address the problems that will arise as a result of intentionally-mandated vulnerabilities in encryption technologies.

We must work together to ensure that the technologies we use every day are able to protect user security the best way they can – through strong encryption. Policymakers should defend the ability of technologists to continue building services and devices that rely on encryption, including end-to-end encryption. Users should make an effort to use these secure technologies, and we should all push back against attempts to weaken encryption.

Want to learn more about encryption, and what steps you can take to stay secure online? We’ve created the following resources with our partners:

Take these six actions to protect encryption and protect yourself.