A young person scrolls through Instagram to see the latest updates on their favorite profiles. To many around the world this doesn’t seem strange, but for a hamlet outside of a small village in Indonesia’s rural southwest, it’s revolutionary. And it’s in part thanks to the work of an Internet entrepreneur named Gustaff Harriman Iskandar.

An artist by trade and passion, Iskandar delved into the technology realm out of a desire to tie artistic works to the world through the Internet. That crossroads, combined with his schooling in the Fine Arts Department at the Bandung Institute of Technology, where he befriended many engineers and technology specialists, soon culminated into an interest in providing Internet access to others in Indonesia. He uses his communication skills to facilitate projects like a community network in Ciptagelar.

“I only have a very average understanding of the tech world and the Internet,” he said. “I find myself having interest in working with people and recognizing other people’s skills and interests. My ability is coming from my artistic background where I develop my artwork with a participatory approach.”

Iskandar has been working to connect technology and art starting back in the late 90s. This background makes him particularly suited to help in Ciptagelar, a small Indigenous village surrounded by dense forest, where his work facilitating policy around ecotourism eventually led him to promote connectivity.

“Our shared interest is Internet.”

The village needs tourism to bring money into the local economy, but its natural environment must be preserved, so visitors are encouraged to travel responsibly and help improve the lives of the local people rather than ignore them or change the environment in any way. The Internet can help get that message to the public.

“How they protect the forest in order to increase their resilience to the rise of population is important,” Iskandar said. “They protect the forest because they need to protect their culture. Our shared interest is Internet.”

Iskandar creates teams out of strangers. His main project, The Common Room, started as an art sharing platform and community center and evolved into a nonprofit that works with governments, communities, and other organizations to fund and accomplish Internet-based projects. They did this in Ciptagelar, where his team consists of friends and acquaintances from his ongoing and growing network.

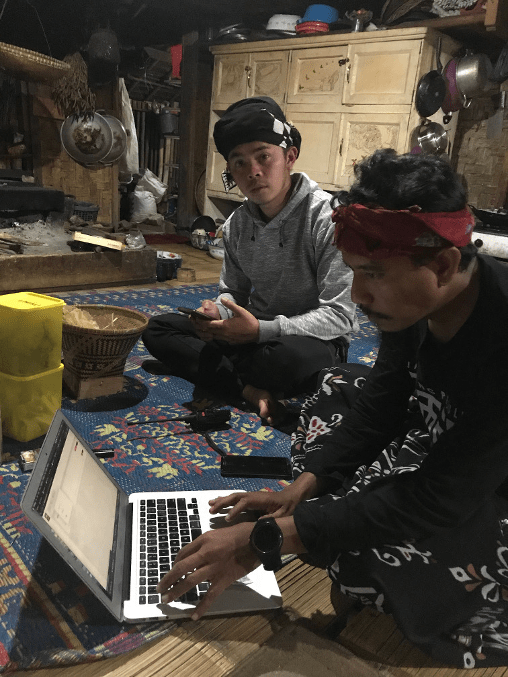

“It’s like a melting pot and a meeting point for people of different backgrounds to collaborate together,” he said. “We involved local ISP communities, some nonprofits, some friends from the government. My role is mostly like matchmaker. I identify problems and challenges, and find solutions by involving people with different talents and backgrounds.”

The Common Room now functions as any nonprofit would, with a board of advisors and several operational teams. They meet every couple of years to see what they have developed, but also to determine what they will develop in the near future.

“One of the biggest parts of the process is my intuition,” Iskandar said. “The other is social media. If I have ideas, I just throw stuff to Twitter or Facebook, my friends give response, we get discussions going, then we start making written plans and ideas. The Internet gives you a lot of tools to play with and provides everything you need to collaborate. Sometimes these people are total strangers who have interest in my ideas. Sometimes they are long-term friends who have a specific interest at the right time.”

Once people sign on, the Common Room develops the framework for those projects and activities, shift their direction, and set to work until they meet again. Right now, they’re focused on connections between urban and rural communities, including building and running community networks.

People’s Needs First: Connecting Rural Areas

To connect rural areas, Iskandar and his team set up community networks with the village chief leaders at the helm. He says in many areas, governmental support is necessary in terms of licensing and regulation that allow communities to build their own infrastructure and use spectrum. Once people can set up their own access in line with existing regulations, they can provide Internet for their underserved communities, and help overcome the digital divide seen particularly on remote islands.

“We bring some equipment, but it is a very stiff area,” Iskandar said. “It is off road, so we have to be careful. One car burned recently when there was a problem with the engine, and we have some broken tires. Sometimes it is a very intense experience, but we enjoy it. The people in the village have some kind of excitement because the Internet connectivity helps them communicate and embrace new opportunity.”

To close the connectivity gap, Iskandar says, they need local leadership to take initiative, and they need the social cohesion and inclusion of the residents.

“So, for us, when a chief leader from an Indigenous community has a strong will to do this, to have more access to information, that kind of will is exceptional,” he said, “and we are now trying to convince the village administration to accommodate these ideas and expand connectivity.”

“Start with one village, expand to six, now keep on going.”

Iskandar starts with just one, he said. His team works together with the community to build a backhaul tower or to connect fiber optics, and they teach the community how to use and maintain this infrastructure as they go. Iskandar says there is a specific formula that makes everything simple: low cost, low maintenance, low energy use with micro-hydro (which is a type of hydroelectric power that uses the natural flow of water for villages that don’t have much energy supply), low learning curve (meaning easy to understand and learn, not complex in terms of technical setup), and local support.

“Indonesia is too big, so people have to find a way to fill their needs with local infrastructure,” Iskandar said. “We cannot rely on government and industries or corporations for this. We need to take it into our own hands.”

The Internet Becomes a Lifeline

In the rural areas of Indonesia, like Citpalgar, Internet connectivity and access often take a backseat to more pressing infrastructure matters like roads and water availability. People live with the bare minimum, and often find themselves secluded from the world, physically and otherwise.

“In Indonesia, when it comes to policy, most people working in government have ideas of connectivity that don’t really help the people,” Iskandar said. “They don’t put priority on the people’s needs. They just want to do things that are more tangible. Internet is not yet a priority.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has pushed community networks development into a priority, he added. Iskandar has been working with rural communities since March 2020 to increase awareness of the virus and provide public education materials in local language. They’ve coordinated with local leaders to initiate a pandemic response, if necessary, and have been deploying local Internet infrastructure to isolated areas which previously could not be accessed at all.

“We are applying the protocols in anticipation,” Iskandar said. “Up until now, we are quite happy to say that the villages we are working with are in the green zone,” he mentions, referring to a public measurement meaning these places were still not in a critical state in the fight against COVID-19.

Iskandar has managed to connect an average of 1,000 daily Internet users in the smaller hamlets and villages in the southern coastal region in West Java Province. With hundreds of villages there, and 25-30,000 people, there is still a lot of work to do. He intends to expand into the southern coastal radian this year.

“Start with one village, expand to six, now keep on going,” he said. “One by one, in each village, the connection is growing. This is helping local businesses and creating new jobs. We are seeing the initiative grow.”

Iskandar says that with the help of the Internet Society, people like him can do the work in the rural areas, not only in Indonesia, but across the globe.

“[The Internet Society] can help to influence these initiatives in many countries by providing the knowledge and helping us to push the agenda on a policy level. They help with sources and funding support to underserved areas in remote places,” he said. “We need a good story to tell to inspire people to do the same movement and initiatives where they are.”

His day-to-day consists of running projects and activities through Common Room, taking care of his two teenage daughters, and running a farm in his hometown that he inherited from his family.

“I always dreamt myself that I would go to Sukabumi, my hometown, well known for its agriculture because of its fertile soil,” he said. “We grow rice, spices. I used to plant ginger and corn. In the near future, my personal plan is to combine traditional farming knowledge with new technology.”

Before he moves into agriculture entirely, he wants to leave the rural areas of his country with a roadmap for building community networks themselves.

“We are now working to prepare a comprehensive guideline, how to build your own community networks, then we will do trainings and facilitations, so other people and groups can build these in other parts of Indonesia.”

All in all, more people in more areas of Indonesia will have access to the wealth and knowledge of the global exchange because of the work of one artist and his vast network of friends and volunteers.