Executive Summary

The Internet of Things (IoT) carries enormous potential to change the world for the better. Projections for the impact of IoT on the Internet and the global economy are impressive, forecasting explosive growth in the number of IoT devices and their use in a wide variety of new and exciting applications.

At the same time, with billions of IoT devices, applications, and services already in use, and greater numbers coming online, IoT security is of utmost importance. Poorly secured IoT devices and services can serve as entry points for cyberattacks, compromising sensitive data, weaponizing data, and threatening the safety of individual users.

These risks and rewards are being carefully considered by many governments and global organizations. However, given the Internet’s global reach and impact, it is critical that its security be addressed collaboratively. That is why the Canadian Multistakeholder Process: Enhancing IoT Security initiative was launched.

Recognizing the complexity of mitigating cyber security risks from the global proliferation of IoT and the resulting necessity for a made-in-Canada policy to address these risks, the Internet Society, in partnership with the Ministry of Innovation Science and Economic Development (ISED), the Canadian Internet Registration Authority (CIRA), Canadian Internet Policy and Public Interest Clinic (CIPPIC), and CANARIE, undertook a voluntary multistakeholder process for the development of broad-reaching recommendations to enhance IoT security in Canada.

This initiative brought together a multistakeholder group — drawn from the Canadian Internet community — to explore both the scope of challenges and the range of promising solutions that could be pursued further to address them, guided by the following principles:

- The complexity of IoT security necessitates a bottom-up, organic process to ensure the outcomes address all existing and potential challenges and issues.[1] The approach should be fluid in nature, defined and refined through discussion with stakeholders.

- Internationally harmonized technical standards are key to enhancing IoT security in the long-term, but they are hard to get right and take time. It is reasonable for approaches to IoT security to start at a national level while working in collaboration with other national, regional, and international bodies.

- Because of the immediacy of the risks and the extended time frame of long-term developments, such as improvements to framework policies and the development of international standards, it is important to start work on educating consumers and for businesses to begin adopting best practices that will reduce the risks of consumer IoT device adoption.

Within this context, the initiative was focused on consumer-level devices as opposed to those that are being utilized at the enterprise level.[2] Throughout 2018 and early 2019, the Enhancing IoT Security multistakeholder group engaged in a series of in-person multistakeholder meetings, focus groups, and webinars and conducted research to develop the following:

- A shared set of definitions and benchmarks around the security of Internet-connected devices.

- Shared guidelines to ensure the security of Internet-connected devices over their lifespan, including the development, manufacturing, communications, and management processes.

- Recommendations to inform national policy related to IoT security in Canada.

A defining feature of the Canadian Multistakeholder Process: Enhancing IoT Security initiative was the use of the multistakeholder approach in its organization, governance, and decision-making. Oversight and guidance were provided by the initiative partners (the Oversight Committee[3]) and management was provided by the Internet Society. Appendix II explores the role the multistakeholder model played in this work and outlines key learnings from the process.

Three thematic working groups, Network Resilience, Device Labeling, and Consumer Education and Awareness, were established to inform the process and to develop specific recommendations. The recommendations of these Working Groups cover the technical, policy, and behavioural aspects of IoT security.

Best Practices, Recommendations, and Next Steps:

Certain aspects of IoT security are so well-established that they were asserted as baseline actions that must be taken to enhance IoT security, including the following:

- No universal or easily guessed pre-set passwords.

- Data should be transmitted and stored securely using strong encryption.

- Data collection should be minimized to only what is necessary for a device to function.

- Devices should be capable of receiving security updates and patches.

- Device manufacturers should notify consumers if there is a security breach.

- Device manufacturers should ensure consumers are able to reset a device to factory settings in the event of a sale or transfer of the device.

Over the course of a year, the multistakeholder group and the Working Groups worked together to develop the following over-arching recommendations:

- Elevate the focus on international-level standards. Standards can provide clear, testable, and credible guidance on implementing security and privacy by design across all jurisdictions.

- Continue development and deployment of the Secured Home Gateway at CIRA and the Manufacturer Usage Description (MUD) standard at the Internet Engineering Taskforce (IETF) in order to provide network-level approaches to resiliency that can address the challenge of low-cost, foreign-made devices that do not adhere to security standards (which are designed for specific devices and firms).

- Continue to develop a consumer friendly label alongside international-level standards. It is recommended that a label combine static “trustmarks” (such as for CE in Europe, Kitemark in the UK, CSA in Canada) with a live component such as a QR Code that can convey advanced and up-to-date product security information.

- Leverage the multistakeholder group’s core content for consumer education and awareness (the Shared Responsibility Framework). This could be used in efforts or campaigns to raise consumer and industry awareness. With funding, a consumer education campaign could be organized by a multistakeholder group that leverages the network created by this Canadian IoT initiative. The Working Groups also developed more granular recommendations for specific stakeholder groups, identified in the following sections.

On Internet-connected device labeling

Recommendations:

- Develop a security label for Internet of Things (IoT) and other digital products.

- Adopt standards for testing and evaluation of IoT products to assist purchasing decision.

- Promote consumer awareness programs for both product labels and testing.

- Enact a regulatory framework that requires formal testing and evaluation of products.

- Create a flowchart that could be used by manufacturers to determine requirements, and by users to determine label expectations.

An effective security label should combine the consumer trust factor of known “trust marks” (such as CE in Europe, Kitemark in the UK, and CSA in Canada) with advanced and critical product security information that can be updated. The label should convey the key information that formal testing and certification has been performed on the product, and how to access up-to-date critical information on product security features and installation/deployment considerations. Examples of security labels can be found in Section 3.3.

Recommended Next Steps:

- Approach and collaborate with organizations focusing on IoT security and privacy in an attempt to reduce the amount of fragmentation in the market for initiatives and labels to avoid consumer confusion.

- Continue to influence the standards effort through the International Organization for Standardization/ International Electrotechnical Commission (ISO/IEC) for international standards and standards developing organizations with similar projects and interests.

- Collaborate with the Online Trust Alliance (OTA) to approach key vendors and solution providers to raise awareness on the need for security certification and device labels.

- Determine the best organization to provide a formal specification of the “live label.” This could be Internet Engineering Taskforce (IETF) or similar, and includes further developing the live label (QR Codes) proposal through collaborating with other organizations such as OTA.

- Elevate the proposed voluntary labeling framework as a model for consumer IoT device manufacturers to demonstrate their compliance with existing Canadian law and regulations in this space.

- Further assess the certification and testing of applications that control devices and backend support services, in addition to focusing on the devices themselves.

- The development of labeling concept should continue. Labeling can be incorporated as a ‘control’ as part of IoT security-related standards being developed at the national/regional (T200) and international (SC27030) level.

There is a need for a regulatory framework for required formal testing of standards and mutual recognition options between IoT standards, similar to the type of agreements that govern telecommunications equipment.

The Device Labeling Working Group proposes that a security product label should include the following:

- Identification of the organization overseeing/authorizing the certification and formal testing (e.g. BSI Kitemark, CE mark, CSA mark).

- A machine-readable code that is linked to a website providing up-to-date product information (i.e., a live label). The website should include the following:

- Product model and/or version number

- Latest product firmware version number

- Recent vulnerability information

- Certification/testing framework

- Security configuration guide

- Information on data collection and sharing

- Key information to be conveyed by the label:

- Formal testing and certification have been performed on the product.

- Where to get up-to-date critical information on product security features and installation/ deployment considerations.

The next steps for implementation must be carried out by many stakeholders, including, but not limited to:

- IEEE Data Port (free resource of large datasets to be fed into the process).

- Vendors, security experts, consultants.

- Civil society, to add consumer perspectives to the standards discussion.

- ISED and government technical experts who can influence the standards discussion to provide public policy considerations, including implication legislation and enforcement.

On consumer education and awareness

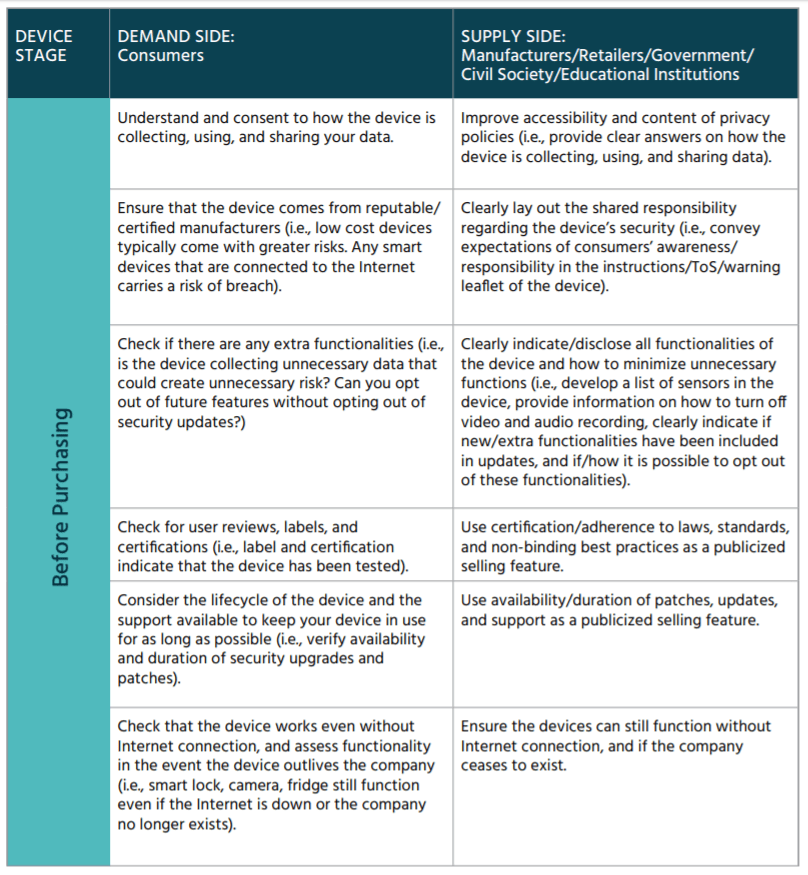

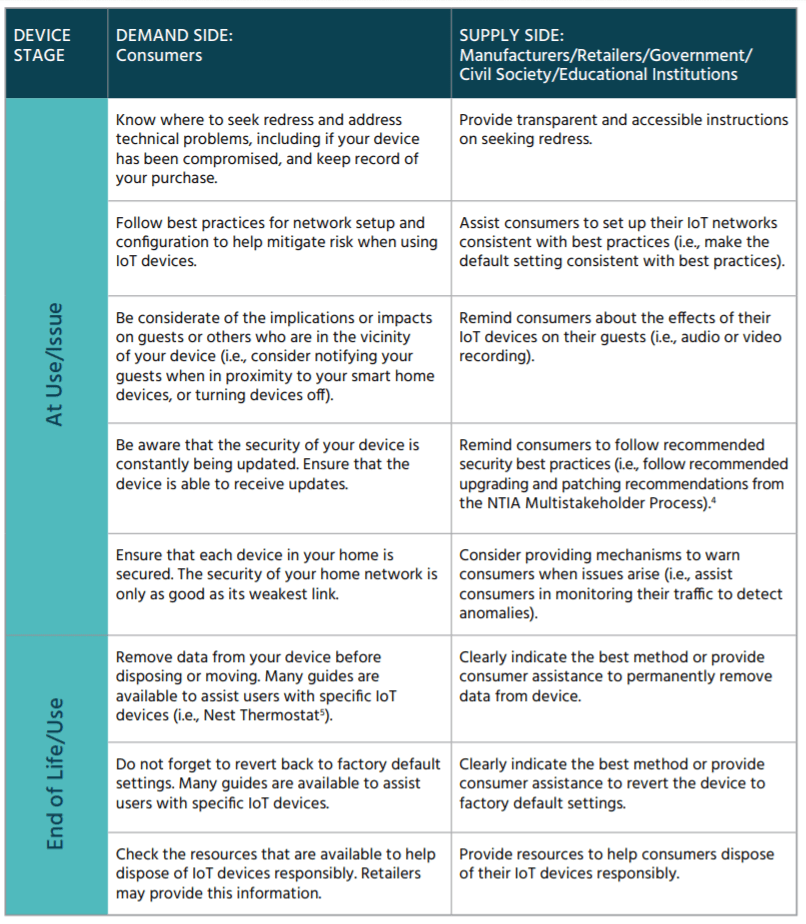

The Consumer Education and Awareness Working Group developed a Shared Responsibility Framework which recommends behaviours for consumers and industry. The Working Group recommends that the Implementation Working Group focus on how to take the content of the Framework, as well as related messaging in the other working groups, to further develop and ultimately raise consumers and industry awareness.

Shared Responsibility Framework

Recommended Next Steps:

- Task the Implementation Working Group with focusing on the delivery of these messages—i.e. convene interested civil society, consumer advocacy, educational institutions, outward-facing Canadian government departments such as the Office of Consumer Affairs (OCA), Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (CCSE), Public Safety Canada, and the Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC).

- Task the Implementation Working Group with providing a multifaceted coordination function, including providing a network where stakeholders could:

- Continue dialogue and networking to ensure consistency of messaging.

- Share opportunities to input into relevant government processes (e.g., consultations, legislative reviews etc.).

- Share their own ongoing IoT-related educational efforts.

- Seek support on how to engage their own membership.

- Coordinate engagement with industry.

- Collaboratively develop an educational campaign (including pooling resources and distribution channels).

On enhancing network resilience

Recommendations:

- The Secure Home Gateway code should be accepted by the core openWRT[6] project. Furthermore, the openWRT should be bundled by default with its IoT security framework, and/or that when manufacturers upgrade their openWRT software, it comes equipped with this framework.

- Future work is needed regarding network resilience with regard to IoT security, including:

- Security evaluation of any new security/user interaction mechanisms. New MUD-based access controls represent significant new attack surface and must be analyzed and tested.

- Continued implementation of a security framework and the integration and development of:

- Device fingerprinting

- Automated MUD profile generation

- MUD clearinghouse

- Access controls

- User controls (visibility, permissions, notifications)

- Unified onboarding

- DDoS Open Threat Signaling (DOTS)-based DDoS filtering

- Quarantine and un-quarantine procedures

- Standards development

- Live labels: integration of live label with network onboarding, MUD, user-interaction

- Out of support notification/device management

- Credential management on IoT devices

- Quarantine/unquarantine

- (MANRS[7] -inspired) MARIS: Mutually Agreed Norms for Internet Security

- Continued global coordination towards standardization, implementation, and adoption

Recommended Next Steps:

- In collaboration with partners, CIRA will continue developing a functional Secure Home Gateway prototype initiative and standard APIs on:

- SHG onboarding

- IoT device onboarding/management

- Device quarantining

- Device un-quarantining

- In collaboration with partners, CIRA will attempt to get two distinct “running code implementations” that are based on the standard APIs.

- CIRA, in collaboration with the two other Working Groups, will submit Internet drafts for MUD extension to support live labels, privacy notification, user space, IoT device management framework, instant management, and credential management.

- CIRA’s Secure Home Gateway initiative will assess integration with Mozilla’s Web of Things initiative.

- Ensure CIRA’s Secure Home Gateway code is available on GitHub, is open source and freely available to all.

- Integrate the work of this group with the Labeling and Consumer Education and Awareness Working Groups.

- This working group will reconvene to assess feasibility, new partners, resources required, and to adjust the plan as needed. It will create a mailing list for notification of updates to this work.

- Raise awareness of stakeholder group recommendations and demonstrate to gateway developers, through the Secure Home Gateway initiative, that these recommendations are achievable, thus providing the larger industry with a framework for secure device development.

Youth-focused recommendations and areas for further research

- Education: For youth in particular, education policy is critical. Provincial/territorial and federal governments should work together with civil society organizations on curricula and programs that can offer forums for discussion and awareness of IoT and other tech-related issues across Canadian educational institutions.

- Conversation: One of the strengths of social media as a medium of engagement is its ability to bring people into a conversation and generate widespread interest in specific topics or events through the multiplying effects of personal networks. Catalyzing authentic personal interest and curiosity through open dialogue which connects a specific issue like IoT security to broader social narratives or concerns is the most effective means of spreading awareness and inspiring action.

- Exploration: Effective engagement and capacity building will also require a deeper dive into assessing the current state of young people’s interaction with digital platforms and their knowledge of them.

- Improving diversity and multistakeholder access: Engagement opportunities should be promoted, and not skewed to certain types of organizations over others.

- Embed participation: Avoid requiring significant amounts of additional time from people by incorporating opportunities to learn about and engage with IoT and other emerging technologies, as well as to participate in policy making, into regular education or training activities.

- Policy changes: Policymakers from around the world can use the best practices of existing and proposed regulation to inform and inspire the basis for an approach to data protection for IoT devices.

- Collaboration: Internet governance and policy involves a variety of organizations from a myriad of backgrounds. The topic of IoT security spans multiple interrelated issue areas, each serving as the focus of a number of these groups. In order to prevent duplication of efforts, collaboration and harmonization must increase between these groups at both the community and international level.

The Enhancing IoT Security Implementation Working Group

An Implementation Working Group, made up of members of the OC, WGs, and multistakeholder group, was formed at the sixth and final multistakeholder meeting to ensure the recommendations are implemented and to carry out next steps. Stakeholders will leverage this group to coordinate and contribute to:

- A coordinated education and awareness campaign on consumer IoT that uses the Shared Responsibility Framework.

- Canadian participation in national and international standards processes—with specific emphasis on engaging and facilitating the contributions of consumer organizations, civil society, and youth — in particular the development of T200 into a binational standard, the ISO/IEC 27000 series, and the IETF MUD standard.

- Canadian participation in international IoT security initiatives, integrating or adapting the trajectory set out by the recommendations and input on the final report. This includes the Internet Society IoT Policy Platform,[8] IoXT,[9] IoT Alliance Australia (IoTAA),[10] EU’s Cybersecurity Act implementation, etc.

- The development of the Secure Home Gateway, binary security label, and related standards.

Notes

[1] A multistakeholder process is particularly well adapted to discovering insights when the dimensions of the issue are not clear; when the solutions are undetermined; and when in general people do not have the answers, there is no consensus around the possible answers, or approach is lacking.

[2] Participants reached near consensus to define IoT as “any network-exposed device not historically accessible, or any device transmitting data, via the Internet, which generally lack sufficient built-in security to protect themselves from causing or becoming a source of harm.”

[3] See Appendix I

[4] https://www.ntia.doc.gov/files/ntia/publications/ntia_iot_capabilities_oct31.pdf

[5] http://www.imove.com/blog/how-to-switch-nest-thermostat-accounts-when-you-move/

[6] “OpenWrt is an open source project for embedded operating system based on Linux, primarily used on embedded devices to route network traffic.” From Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/OpenWrt

[8] https://www.internetsociety.org/iot/iot-security-policy-platform/